What is an Implantable Cardioverter Defibrillator (ICD)

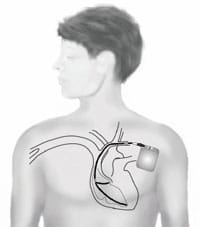

An implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) is a medical device to treat life-threatening heart rhythm abnormalities. It consists of a small box containing a battery and electronics that is inserted under the skin and wires (‘leads’) that are most commonly passed through the bloodstream into the heart but can also remain under the skin (see subcutaneous Implantable Cardioverter Defibrillator, left).

ICDs can treat heart rhythm problems in three ways: firstly they can act like a pacemaker delivering extra signals to the heart to prevent it beating too slowly; secondly, in the event of a dangerous fast heart rhythm the device can deliver a short burst of signals (Anti-tachycardia pacing, ATP) that may return the rhythm to normal; finally, if ATP fails to terminate the abnormal rhythm a large pulse of energy (cardioversion, commonly referred to as a shock) can be delivered to restore the normal rhythm. ICDs have been in common use for more than 20 years and have been proven to extend the life of people of have survived a previous cardiac arrest or who are thought to be at high risk of having a cardiac arrest due to an underlying condition.

Who needs an ICD?

ICDs are recommended for people who have either survived a life-threatening abnormal heart rhythm, or who have a condition where the risk of a life-threatening abnormal rhythm is high. The most common reason people in the UK need an ICD is related to previous heart attacks and subsequent weakening of the heart muscle (ischaemic heart disease and ischaemic cardiomyopathy). However, in young people ICDs are more commonly recommended for people with problems with the heart muscle (cardiomyopathies) or electrics (ion channelopathies). These conditions include: hypertrophic cardiomyopathy; arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy; dilated cardiomyopathy; long QT syndrome; Brugada syndrome. Not everyone with these conditions has a high risk of life-threatening heart rhythm abnormalities and the decision to implant an ICD is taken on an individual basis. There are a number of factors for each condition that are known to signify an increase to a person’s risk an you should discuss these with your cardiologist if you have any of these conditions.

How are ICDs implanted?

Implantation of an ICD is a safe procedure with a very small risk of complications. It is similar to implantation of a pacemaker. Implantation usually takes around 1 hour and you will most likely stay in hospital overnight before being discharged the following day. The procedure is carried out in a cardiac catheter laboratory, a room similar to an operating theatre. There will be several people present during the procedure including a doctor, nurse, physiologist and radiographer. An anaesthetist will also be present if the implantation is being carried out under general anaesthetic, although this is not always required. If general anaesthetic is not used a combination of local anaesthetic and sedating medication is used. You will be given a dose of antibiotics before the procedure to minimise the risk of infection.

Once anaesthetised, an incision is made, approximately 10cm long and most commonly under the left collar bone. A needle is passed into one of the veins around the left shoulder and the leads are passed into the heart via this vein. There may be one or two wires depending on the type of ICD. X-rays are used to guide the leads in to the heart and ensure they are in the correct position. Electrical tests will be carried out to ensure correct positioning. Once the leads are in place they are stitched in under the skin of the collar bone and the ICD box is attached. A ‘pocket’ is created between the skin and underlying muscle (occasionally the pocket is created below the muscle) and the box is inserted. The skin incision is then closed with 2 or more layers of stiches.

At this point the ICD may be tested by putting the heart in to an abnormal rhythm and monitoring closely to ensure it correctly detects the abnormal rhythm and delivers the appropriate treatment. This is referred to as ‘defibrillation threshold testing’ or DFT. Not all hospitals perform this step and you should discuss this with your cardiologist prior to implantation.

Following the procedure an x-ray will be taken and further electrical checks performed to ensure the leads remain in the correct position and the system is working correctly.

You will have an appointment 4-6 weeks later to check that the wound is healing well and check the performance of the ICD. The device’s memory will be interrogated as it records any episode of abnormal rhythm and of the treatment delivered. Many ICDs now have the function to be able to transmit such information to the hospital via a home monitoring system (often referred to as remote monitoring or tele-monitoring). This may reduce the number of routine follow-up appointments at the hospital but is not always available or suitable. You should ask your cardiologist about what services are available.

The average battery life of an ICD is around 7 years, although this is improving with newer technology. Once the battery is nearing expiry you will need to have a further procedure where the existing ICD box is removed and replaced (an ‘elective unit replacement’, often referred to as a ‘box change’). Unless there is a separate problem, the leads will remain in place making this procedure even safer and more straightforward.

What are the complications of ICDs?

Complications related to ICDs can be separated into two types: complications arising from the implantation procedure and long-term complications of the device function. Complications of the implantation are unusual and are similar to those complications of pacemaker implantation. The most important risk is on infection. Infection of the ICD can spread to the heart via the leads and require the removal of the ICD and leads and a significant period of time taking antibiotics. Therefore everything is done to minimise the risk of infection including sterile technique for implantation and antibiotics used routinely on the day of the procedure. The approximate risk of infection is 1%. Depending on which vein is used to access the bloodstream, there may be a risk (around 1%) of causing a small puncture to the lung (a pneumothorax) as the veins can sit very close to the top of the lung. If this happens it will often heal by itself but sometimes a chest drain is needed to help the lung re-inflate. Bruising around the incision is common but significant bleeding is very rare. Occasionally the leads may move or displace after the implantation requiring a further procedure to reposition them.

The most important long-term complication of ICDs is that of inappropriate shocks. That is when the ICD mistakenly thinks that the heart is in an abnormal, life-threatening heart rhythm and so delivers a shock to treat it when in fact there is no danger. Situations that can confuse the ICD include: when the leads are damaged so they do not detect the heart rhythm normally; naturally very fast heart rates due to exercise or intense emotion; other non life-threatening heart rhythm abnormalities such as supra-ventricular tachycardia (SVT) or atrial fibrillation (AF). In the event of inappropriate shocks the ICD can often be re-programmed to avoid the particular problem. However, if the leads are damaged, replacement if often required. Failure of the ICD to correctly detect a true life-threatening rhythm is very rare.

Can there be problems living with an ICD?

An ICD is not a cure and does not treat the underlying condition for which it was implanted. It’s role is to protect you if you should ever have a life-threatening abnormal heart rhythm. You may still need treatment for your underlying condition or have other symptoms that the ICD does not help.

People can sometimes find living with an ICD difficult and can become anxious or depressed. Common worries include concerns about the device not working correctly, or about receiving shocks and about feeling embarrassed should you receive a shock in public. People are also sometimes concerned about the impact on having a family or on work. You are not allowed to drive for 6 months after the ICD is implanted and there may be further restrictions if you receive a shock. These worries will be worse if you do not have someone of your own age or background to talk about things with and therefore CRY’s myheart Support Network is strongly recommended to help work through some of these concerns. There are lots of young people who continue to lead happy and fulfilling lives after their ICD has been implanted

You can lead a full and active life with your ICD!