What is Brugada Syndrome?

Brugada syndrome is a rare genetic heart condition that disrupts the heart’s normal rhythm, leading to abnormal heartbeats in the lower chambers (ventricles), a condition known as ventricular arrhythmia. First identified in the early 1990s, Brugada syndrome is relatively uncommon in the Western world but is more prevalent among young men in Southeast Asia. In the West, it primarily affects young and middle-aged men.

Causes of Brugada Syndrome

Brugada syndrome is often linked to mutations in genes that control the sodium, calcium, and potassium channels of the heart. The most common mutation involves the SCN5A gene, which affects the sodium channel and is responsible for around 20% of cases. This mutation restricts the movement of sodium ions into the heart cells, resulting in characteristic changes on an ECG but no structural abnormalities of the heart. Other genes related to calcium and potassium ion channels have been found in some carriers, though they account for a smaller number of cases.

Brugada Syndrome Symptoms

While many individuals with Brugada syndrome remain symptom-free, others may experience:

- Blackouts (syncope): Sudden loss of consciousness due to irregular heartbeats.

- Palpitations: Sensations of rapid or irregular heartbeats, often caused by ectopic (extra) beats.

- Sudden Cardiac Arrest: In severe cases, Brugada syndrome can lead to life-threatening arrhythmias, including ventricular fibrillation.

Signs of Brugada Syndrome

Brugada syndrome typically has no visible physical signs. The only indications are abnormal patterns that may appear on an ECG, especially during times of stress, fever, or after taking certain medications.

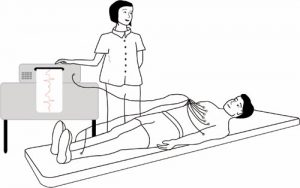

Diagnosis of Brugada Syndrome

The primary tool for diagnosing Brugada syndrome is an electrocardiogram (ECG). However, ECG changes can be inconsistent; they may appear continuously, intermittently, or not at all. Fever or specific medications can trigger the characteristic ECG pattern, and this may signal a period of increased risk for fainting or cardiac arrest.

If Brugada syndrome does not show up on a standard ECG, a provocation test may be used to unmask the condition. This involves administering an anti-arrhythmic drug (e.g., ajmaline or flecainide) while monitoring the ECG for changes. However, even with a provocation test, not all carriers of the genetic mutation will show abnormal ECG results, leading to some debate about the reliability of negative results.

Genetic Testing can also be useful, though it only identifies a small proportion of people with the syndrome.

Management and Treatment of Brugada Syndrome

Managing Brugada syndrome focuses on reducing the risk of life-threatening arrhythmias. Here are some key strategies:

- Avoiding Certain Medications: People with Brugada syndrome should steer clear of medications that can exacerbate their condition.

- Managing Fevers: High fevers should be treated promptly with paracetamol or ibuprofen to prevent triggering an arrhythmia. In severe cases, hospital monitoring may be required.

- ICD (Implantable Cardioverter Defibrillator): For individuals who have suffered a cardiac arrest or fainting episodes, an ICD may be recommended. This device monitors heart rhythms and delivers a shock if a dangerous arrhythmia occurs.

- Quinidine: In severe cases, quinidine, an anti-arrhythmic drug, may be prescribed alongside an ICD. Its role in Brugada syndrome is still under investigation.

Challenges in Treatment Decisions

Deciding on treatment for asymptomatic individuals with abnormal ECG results can be difficult. An electrophysiological (EP) study may help assess the risk of arrhythmias and determine whether an ICD is necessary, though its value is debated. Research suggests that people with normal ECGs and no symptoms generally have a lower risk and may not require treatment. It is rare for children with Brugada syndrome to be at high risk of serious complications.

Brugada Syndrome and ECG Monitoring

Monitoring your heart health with regular ECGs is crucial for people with Brugada syndrome, particularly if symptoms like fainting or palpitations occur. Continuous monitoring and awareness of triggers such as medications and fever can significantly reduce the risk of complications.

For more information on managing Brugada syndrome, consult a healthcare provider, and consider a genetic test if you have a family history of the condition.

CRY Consultant Cardiologist Professor Sanjay Sharma talks about Brugada syndrome below. This video was published in 2011 – please note that the incidence of Brugada is now (July 2017) considered to be 1 in 2,000.

Management – Brugada Syndrome

All carriers of Brugada syndrome should avoid certain medications that might worsen their condition. They are also advised to avoid low blood potassium levels, known as hypokalaemia, and should treat all fevers with medications that reduce their body temperature such as paracetamol or ibuprofen. If their fever remains high they should attend hospital for an ECG or monitoring as required.

It is standard practice for people who have suffered a cardiac arrest or a blackout to have an ICD fitted as this is a very successful form of protection. The tablet quinidine has been used in some patients with severe disease and an ICD already in place but its exact role remains under investigation.

Unfortunately it can be very difficult for doctors to decide how to treat those people who do not get symptoms but who have an abnormal ECG. An electrophysiological (EP) study may help to identify those people who do or do not need an ICD although there is great controversy about its true value. Research has suggested that most people with normal ECGs and no symptoms should be safe without any treatment. It is unusual for children to be at high risk.