‘Grief like this can drive you insane’

‘Grief like this can drive you insane’

Daily Telegraph (used with kind permission) – 2nd May 2005

By Elizabeth Grice

It was one of those chaotic bedtimes. As Howard English kissed his wife, Stephanie, goodbye and set out for his evening rugby training session, he teased her about escaping from the domestic mayhem, leaving her to cope with three boisterous young children. They parted laughing.

Not long after, she received a call from his trainer. Howard had collapsed on the pitch and been taken to hospital. She should get there fast. He was always breaking his collar bone, but this sounded more serious. When she arrived, Howard was still connected to the resuscitation equipment, but its use had been futile from the start. He had died instantaneously on the field – a 32-year-old, super fit sportsman in his prime whose heart had inexplicably stopped.

Not long after, she received a call from his trainer. Howard had collapsed on the pitch and been taken to hospital. She should get there fast. He was always breaking his collar bone, but this sounded more serious. When she arrived, Howard was still connected to the resuscitation equipment, but its use had been futile from the start. He had died instantaneously on the field – a 32-year-old, super fit sportsman in his prime whose heart had inexplicably stopped.

“It was so terrible, so bad, I had no words for it,” she says. “There was no warning at all. What breaks my heart is that Howie was such fun, such a wonderful father. He loved life and I loved him so much.”

They had known one another for 12 years, been married for six, and assumed they would grow old together. Now, she was barely 30 and left to bring up three children under five. On her way to the hospital, Stephanie says she had a premonition that Howard was dead. Even so, seeing him was unreal. “I felt so sick. My legs went. I felt I was not really there. He had a slightly surprised smile on his face, but he was absent. I remember thinking, ‘This can’t be happening.’”

But it was. And 11 years later, it was happening all over again. Last year, in almost identical circumstances, their eldest son, Sebastian, collapsed and died. Like his father, the 15-year-old had been playing rugby. As the ball rolled out of touch, he went to retrieve it, then keeled over. It was like some black action replay. “The devastation to our whole family was simply awful,” says Stephanie. “People found it unbelievable. They did not know how to treat us. This kind of grief can drive you insane. I can understand why some people go mad.”

But it was. And 11 years later, it was happening all over again. Last year, in almost identical circumstances, their eldest son, Sebastian, collapsed and died. Like his father, the 15-year-old had been playing rugby. As the ball rolled out of touch, he went to retrieve it, then keeled over. It was like some black action replay. “The devastation to our whole family was simply awful,” says Stephanie. “People found it unbelievable. They did not know how to treat us. This kind of grief can drive you insane. I can understand why some people go mad.”

The parallels were so shocking that Stephanie knew it couldn’t be coincidence. Perhaps the cause of her husband’s death – said to be floppy mitral valve disease – had been misdiagnosed? Could father and son be victims of some genetic disorder? And, if so, would it claim the lives of their two other children, Sabrina and Titus?

Many tense months later, her suspicions have been borne out. Howard’s 84-year-old mother has been found to have the same mutant gene as her grandson, and it was only a matter of time before tests on Howard’s tissue, retrieved from the post-mortem, showed he had it, too. It’s now known father and son died of arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy (ARVC), an inherited condition affecting one in 10,000 – usually fit, active men between 14 and 35.

“If you have a sudden unexplained death in the family, you know it’s irrational to feel guilt,” says Stephanie. “But I do feel that about Sebastian. He didn’t need to die. If the cause of Howard’s death had been accurately determined, if we had been aware of abnormal genetic heart conditions, if Sebastian had been effectively screened, he could probably have had a defibrillator fitted and he would still be with us. He was a wonderful boy, warm, generous, fun, sporty, clever – and a true friend. The younger children adored him. It was such a dreadful waste.”

People said the same about Howard English. He was a party animal, an active father, an outrageous joker, the sort of man who could raise your spirits just by walking into a room. John Inverdale, the rugby commentator, who was playing rugby with him at Esher when he died, recalls English clubbing into the early hours, then driving through the night to get to a rugby game in Cornwall.

“He’d been to Annabel’s or somewhere and arrived at the last minute, still in his suit. He hadn’t slept, but he played a brilliant game, was man of the match and led the singing. We got hardly any sleep that night either, but the next morning Howard was at the piano, playing the Funeral March as each player came in to breakfast. That’s the kind of person he was. He lived life to the full. He was a truly amazing guy and an outstanding player. His was the most joyous funeral service I’ve ever been to.”

Howard English died in Inverdale’s arms at the side of the pitch. “It was a truly shocking, hysterical moment,” says Inverdale. “When he went down, we knew in a split second that something awful had happened. He just didn’t move. When the same thing happened to Sebastian, it was beyond terrible for Steph and the family. Talk about fate dealing someone a rough hand.”

Stephanie says there are still days when she doesn’t know how to go on, but today she seems strong. In fact, when I come to read my notes of our conversation, I see that she has used the word “lucky” no fewer than six times. Lucky that she married another wonderful man, lucky that she had two more children, lucky that they meshed so perfectly with the older children, lucky that there was no argument or family discord on the night Howard left for the fatal game. Above all, lucky that a cardiologist has just confirmed that Sabrina, now 14, and Titus, 12, do not have the mutant gene –plakophilin-2.

“It is a massive thing, knowing they are going to be all right,” she says. “The test was so definitive that they can live their lives without fear. It’s bad enough grieving for Sebastian without fearing for the lives of the other two. If the faulty gene had not been detected early and eliminated, they would have been faced with tests every six months for the rest of their lives. This news has fundamentally changed our lives.”

Within a year of Howard’s death, Stephanie, now 41, married one of his best mates, Rupert Hunter, a 43-year-old investment manager. He had been one of a rota of friends who had visited regularly to make sure she was coping and eating properly. They knew quite soon that they were falling in love, but didn’t dare to acknowledge it because they were afraid others, particularly Howard’s family, might feel they were insulting his memory.

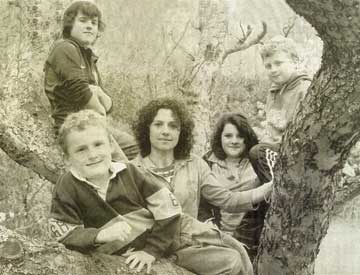

But the news was welcomed by one and all, and they both felt that Howard, a generous spirit, would have approved, too. “We had thought of delaying the wedding,” says Stephanie, “but we knew we wanted to have children and it seemed best if they could be close in age to the other three.” There is only a three-year gap between Titus and his half-brother, Marcus, nine. The youngest, Rory, is six. They are such a harmonious family unit and none of them regards Rupert as a stepfather.

When Sebastian died and colleagues in the City commiserated with phrases such as: “Terribly sorry to hear about your stepson,” or “It must have been terrible for Steph,” Rupert was aghast. “They just didn’t understand. Bas was my son, too,” he says. “He was the talisman of the family. I knew from the start that if I got it right with Bas, I’d get it right with everybody. After we got married, he was the first to say: “I’m going to call you Daddy now. Is that OK?”

The condition ARVC was not classified as a separate disease until 1996, three years after Howard English died. Even now, doctors are in the early stages of understanding it. The condition is usually not detectable until adolescence, and it’s possible to have a genetic susceptibility without ever being affected. Although it occurs in fit, sporty people, strenuous exercise doesn’t necessarily provoke cardiac arrest.

CRY wants the Government to introduce national screening for young people and athletes. In Italy, annual ECGs are mandatory for anyone who plays sport for club, school or region. In Britain, CRY screens rugby and tennis players – but only in clubs and public schools. It is urging the Government to fund screening in all schools.

The movement is gathering momentum. The RFU has started screening young athletes at its Junior National Academy in Bath, and plans to extend the programme to all 14 regional academies. And the Cardiomyopathy Association (CMA) is setting up clinics in Glasgow and Belfast to screen and treat young people with inherited cardiovascular diseases. As Dr Elliott says: “We need to be able reassure those who are unaffected and treat effectively those who are.”