Guy Evans, died aged 17 of a suspected heart arrhythmia while riding his motorbike.

How does anyone begin to describe the pain at losing a precious child suddenly and without any warning?

The evening of August 14th last year (2008) was the last time we saw our beloved 17-year-old twin son, Guy, alive. At around 7pm he came into the house to pick up some things for a sleepover, gave me (his mum) a hug, said a cheery “see you Dad” to his father who was in the sitting room watching TV, yelled goodbye to his brother upstairs – and was gone from our lives forever.

The day he died he was on top of the world and running on adrenaline. In the morning he had learned – with huge relief – that he’d passed three AS level exams. It meant he could stay on at St.Birinus School in Didcot, Oxfordshire, to take his A2 exams and hopefully go on to university or college.

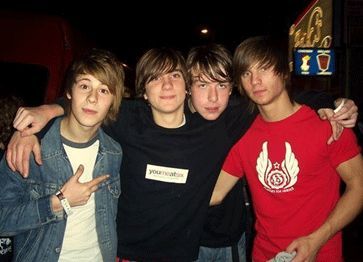

It was also two days after he’d passed his motorbike test and just five weeks after his 17th birthday. When he went out that night he was with three close friends and was simply loving life. He was with the people he loved and doing what he had become so passionate about – riding his new Yamaha 125 racing bike.

No parent takes lightly the fact that their son has developed a passion for motorbikes. We resisted as long as we could his entreaties to let him buy the Yamaha using the money he had assiduously saved up from his part-time job. But we knew he was a safe and sensible rider. He had ridden more than 6,000 miles to and from school in the previous year on his Aprilia moped because our village has virtually no public transport and he needed to get to his lessons. We knew he didn’t take risks, was extremely safety conscious and always looked out for his friends to make sure they were OK.

That night was no different. He and his friends were returning from Wantage as night began to fall. Guy was in front, setting the pace, leading them home safely. At just after 9pm the phone rang. It was Guy’s friend, Matt, who had been riding directly behind him.

Guy, he said, had had a bit of an accident but the paramedics were with him, and not to worry. We didn’t realise then that Matt, deeply shocked, was trying to shield us from the truth. Guy wasn’t OK – he was already dead, lying in a ditch at the side of the road, still partially astride his motorbike, surrounded by young people who were totally bewildered as to what had happened.

Guy’s twin and I immediately leapt into the car and went to the scene of the accident. It was totally surreal. The road was blocked off by a police car and there were flashing lights in the distance. It was like a scene out of The Bill we’d just been watching on TV. The police let us through, but when we got near the accident scene our path was blocked by another police car and several police officers. They didn’t tell me he was dead in so many words – the female officer just kept saying “I’m really sorry”. I now know what true shock feels like.

The rest of that night and the following weeks and months were agonising, a nightmare, unreal. Everyone at the accident scene – police and paramedics alike – assumed that Guy must have hit something in the road, been thrown from the bike and had died of a broken neck or serious injuries. After identifying his body in the early hours of the morning – a terrible experience I cannot bear yet to write about – I was told the post mortem would in all likelihood confirm this view and his body would be released for burial.

But instead of the phone call I was expecting four days later on the day of the post mortem, we instead received a visit from the Coroner’s assistant, the head of the police investigation and the police family liaison officer who had been assigned to us. The post mortem had revealed that Guy had suffered no injuries whatsoever.

The only cause of death the pathologist could find was mechanical asphyxiation – Guy had died simply because he couldn’t breathe.

As I tried to take this in, worse was to come. I was told that the police investigation was now focusing on whether basic first aid would have saved Guy’s life. Just as devastating was the fact that the pathologist, who was not satisfied with what he’d found, had removed Guy’s brain and was sending it to King’s College Hospital in London for detailed examination.

Something catastrophic must have happened to result in such an outcome.For weeks and months we waited for the results.

All the time, we had to face the fact that if no brain trauma or abnormality was found, it was more than possible that Guy’s life could and should have been saved if he’d been given the most basic of first aid. If his airways had been checked to see if he could breathe. If he had been put in the recovery position until help arrived. So many “ifs”.

We knew by then Guy had landed awkwardly, the top half of his body face down in the ditch. We also discovered that during the 999 call, his friends were repeatedly told not to move him. No advice was given on how they might be able to actually find out if he was breathing. No resuscitation instructions were given. The operator didn’t even ascertain what position he was lying in.

The inquest eventually took place seven months after Guy’s death. By then we knew that no significant abnormalities had been found in Guy’s brain. But I felt strongly that something was very wrong here – motorcyclists simply do not suffocate, their helmets are designed to protect their airways, not restrict them.

Throughout all this, we were blessed with having a pathologist who, thank God, wanted to find us some answers. Having looked carefully at all the evidence, he told the court that on the balance of probabilities, he believed that Guy had suffered a sudden fatal heart arrhythmia.

There was no evidence of a major brain trauma, his airways weren’t blocked or damaged, he had no other injuries and he had played no part in the accident. He didn’t move or struggle to breathe or try to extricate himself in any way. My beautiful son was deeply unconscious – his elbow apparently twitched twice and that was it.

After the inquest, the pathologist explained to me about ion channelopathies and how sudden heart arrhythmia is virtually impossible to diagnose after death. It needs a beating heart to be able to test for abnormal patterns, and moreover Guy’s heart had looked completely normal during the post mortem examination.

The pathologist couldn’t say whether attempts to revive him might have been successful. I gather there was possibly a “window” of around three to four minutes before brain damage and death set in but not more. Having spoken to CRY, I now know Guy’s chances of survival on that night were virtually nil.

As we tried to digest the reality of what had happened, I knew instinctively that the pathologist was right. Although Guy always seemed perfectly fit and healthy, in the months leading up to his death he had experienced two or three dizzy spells – a “blood rush to the head” is how he had put it. I didn’t want him on his moped if he was feeling dizzy but he refused to go to the doctor.

He was 17, had shot up several inches in height and not for a single minute did I think that such a common occurrence in teenagers could herald a potentially fatal heart condition. How I wish I could turn back the clock. A few months after the inquest I also suddenly recalled – during yet another sleepless night – an occasion when Guy had placed my hand over his heart. “Feel that, mum” he said. If only I’d known.

But things like this happen to other people, don’t they? Not to us. At least that’s what I had always thought. Guy and his twin were growing up to be fine young men so why would anyone have thought there could be something wrong? Of course, I’d read in the newspapers about young people suddenly collapsing after strenuous exercise and a friend’s 14 year old son had suddenly died in his sleep from a heart problem the previous year. But Guy didn’t play sport. He was happy, full of life and fun, and had everything to look forward to.

This month, a year on from his death, the pain gets worse if anything, not better.

We still cannot believe he is gone. That we will never see him, or hear his laugh, or see his smiling face or cuddle him again. We will never be irritated by his habit of practicing his drumming skills on every surface he could find, including the car dashboard. We’ll never again groan at his cheesy jokes. He wasn’t able to buy his Dad his first legal pint in a pub on what would have been his 18th birthday in July. He’ll never nod his head in respect to other motorbikers on the road or turn up his favourite rock music so loud that the car doors shake.

And the saddest part of all is that we’ll never see him mature into the fine young man he was starting to become. He’s frozen in time – a beautiful 17-year-old whom we would have given absolutely anything to protect, if only we’d known there was something wrong. If only his Dad or I could change places with him – we would willingly do that.

For his friends too, the last year has been so hard. They loved him and would have done anything to save him. We have all tried to accept, hard as it is, that there was virtually no chance of saving him. No-one is to blame and no amount of rage or anger or despair will bring him back.

All I can say as a parent, is that out of this tragedy we want something positive to emerge. Guy’s friends and ourselves are organising a big celebration of his life and his passions of rock music, motorbikes and computer games, to mark his 18th birthday and the first anniversary of his death. We want the event to be fun, a chance to talk and laugh and do the things he liked doing.

And then, when it’s over, we need some peace and quiet and to move forward if we can.

Since Guy’s death, we have begun campaigning alongside organisations such as the St John Ambulance to press the Government to introduce basic first aid into the secondary school curriculum. With the support of our local MP, we’re also in contact with the Department of Transport to press for practical basic first aid sessions to be included in motorbike and motor vehicle tests.

And Guy’s death is already making a difference to the way the 999 service operates. As a result of an investigation into the handling of the 999 call on the night Guy died, the regional ambulance service has accepted that the operator made a fundamental error at the start of the call by not establishing properly whether Guy could breathe or not, and this was then compounded by an inflexible computerised response system from which operators are not allowed to deviate. In other words, Guy’s death has highlighted a serious flaw in the 999 system.

The ambulance service is now reviewing its procedures for dealing with motorbike accident victims and its operator training. It is looking at ways of improving the system – possibly by introducing a separate system of questions for motorbike accidents – and has undertaken to share the lessons with other ambulance services. We are also asking the Health Secretary to instruct other UK ambulance services to do the same.

But none of this frantic activity really helps much right now. In time, when everyone else is getting on with their lives, we know we will have to face our grief alone. We love and miss Guy more than I can possibly say. Like all those who have lost a child this way, our lives have been broken and will never be the same again. But I know his lovely spirit will always be with us, he will be just around the corner, just out of sight. Maybe in time we will accept what has happened and learn to be grateful that he has left an indelible mark on the world he has left behind.

Beth Chesney-Evans – Guy’s Mum